Challenges of process modeling in theory and practice

Introduction

This essay is based on theory of process modeling and the case study conducted in a Finnish nation-wide health care service organization where 112 processes were defined and modeled by 59 employees in 102 workshops. The case organization has totally more than 500 employees. Health care organizations can be regarded as high-reliability organizations, which must continuously perform in a near error-free manner despite their complex, unpredictable and dangerous operating environments (Roberts, 1989; Weick, 1987; Weick and Roberts, 1992; Ray, Parker and Plowman, 2011; Vogus and Welbourne, 2003 ; Gebauer, 2012). Therefore, high-quality descriptions of the processes will in particular help the activities of such organisations.

Theory of Process Modeling

A business process is a “bounded set of activities that are undertaken, in response to some initiating event, in order to generate a valued result” (Harmon 2014, 185). Business process management (BPM) is a management approach that aims to manage the network of the organization’s horizontally flowing processes, thus creating value for customers (Harmon 2014, 6; Rummler & Brache 2013, 58). Processes are visualized to increase joint understanding of activities that form processes and their relationships. This is called process modeling (Luukkonen, et al. 2012, 53).

Major steps of a process modeling project can be divided into two phases: 1) Defining and documenting goals and objectives for the end result and 2) Defining and documenting practical matters relating to project management. These include participants, other resources, goal setting, agreed working methods and division of work in a project (Luukkonen, et al. 2012, 53-54).

Goals and planning of process modeling

Before starting a process modeling project, organization should define and document the goals for the results considering following aspects: (Luukkonen, et al. 2012, 53-54).

- Purpose of process modeling

- Primary use of the process models and other possible later use

- Viewpoint(s) emphasized in modeling

- Modeled version of the state of the process

- Timeframe: schedule, milestones, deadlines and check points

- Prioritization of modeled processes based on purpose and use of the process models

- Scope of the produced documentation, including required level of detail of each process or target area of interest and other required boundaries for modeling

- Common modeling principles: frameworks and modeling levels, notation language, naming of processes, collection of metadata etc.

Good planning of process modeling project is essential, although, process modeling is creative and iterative activity and the unique circumstances have a major effect on the modeling process (Luukkonen, et al. 2012, 53-54). One popular model in Finland is the JHS 152-framework which has been created for the purpose of unifying process modeling in the Finnish public organizations (Luukkonen, et al. 2012, 33).

Different user needs and different level of processes

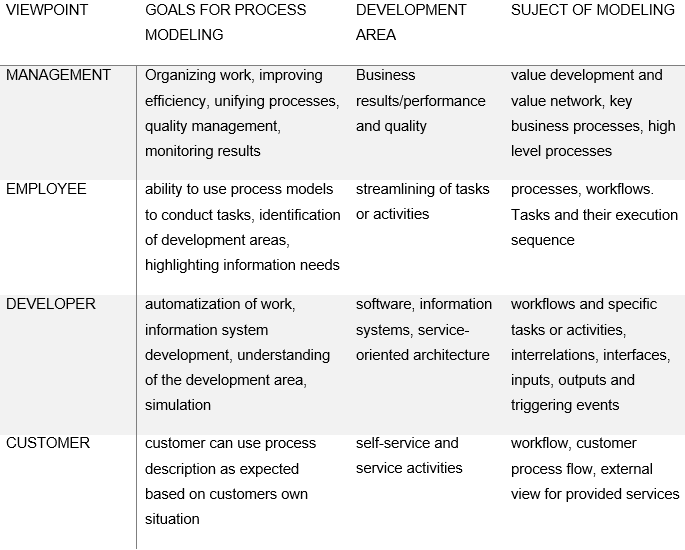

Different organization members or groups have different needs on process modeling based on what those organization members or groups use the process models for, so it can be necessary to model same processes from different viewpoints (Luukkonen et al. 2012, 26-27; Bobrik et al. 2007, 1-2.)

As it’s not sensible to model all processes with the same level of detail the suitable level of detail should be chosen based on the purpose the process model is used for so that it gives enough explanation to understand the process (Harmon 2014, 228; Laamanen 2003, 81). Following Table 1 describes typical aspects that four different viewpoints emphasize in process modeling. It illustrates viewpoints of management, employee, developer, and customer (Luukkonen et al, 26-27).

Table 1. Different viewpoints for process modeling (Luukkonen, et al. 2012, 26-27).

Business process architecture represents the hierarchical structure of the organizations process management (Laamanen & Tinnilä 2009, 87). Business process architecture is composed of the organization’s major value chains, key processes, and the relationships between them. Often it also includes the measures and the governance of the processes. Value chains should include required support processes, management processes and their relationship to core processes. It should be noted that strategies can exist in different levels of the organization (Harmon 2014, 24-25, 54-55, 68-69, 88-89, 94, 159.)

Process modeling project

Process modeling project can be conducted “top-down”, starting from the higher-level processes (less details), or “down-up” starting from more detailed level processes and proceeding to higher level processes (Luukkonen et al. 2012, 56).

Following steps can be followed when identifying and modeling processes (Laamanen 2003, p. 66-67, 89-94):

- Recognize what is the process applied for. It is important to especially recognize the beginning end points of the process.

- Identify customers, their needs and requirements.

- Describe the purpose and goals of the process and what is the role of the process in the organization.

- Define inputs and outputs (products and/or services) and how is the process related information managed. Information could include memos, action plans, technical drawings, manuals, instructions, feedback forms etc.

- After the information gathered from steps 1-4, process is modeled.

- Define central roles, tasks, and key responsibilities of the roles.

Especially more detailed level process models are often modeled in a “swim lane” format (Laamanen 2003, 80; Harmon 2014, 219-220). Usually process models are structured in a way that the activities move from left to right and this movement illustrates the flow of time so that activities placed on a left side happen before the activities on a right side of the model (Harmon 2014, 219).

The minimum goal in business process modeling is to increase the understanding of the organization’s operation and goals (Laamanen 2003, 96). Aim of a process modeling project is to produce process models with satisfactory quality level compared to the intended use (Luukkonen et al., 2012, 54).

Criteria for good process models

Laamanen (2003, p.76-77) determines some simple criteria for a good process model:

- should describe critical factors of the process

- be able to illustrate the relationship between different elements

- enable understanding of the “big picture” and one’s role in achieving process goals

- enhance co-operation

- enable situational flexibility

After the processes are modeled, the models should be evaluated by the people who are working in the processes. Aim is that everyone understands the big picture and how their role fits into that. (Laamanen 2003, 97.) Suitable quality and if applicable, different quality requirements should be defined in the beginning of a process modeling project based on the intended use (Luukkonen et al. 2012, 54).

Maturity level of organization and change management in process modeling project

Change management is essential in implementation of BPM (Trkman 2010; Schmiedel et al. 2013). Problems may occur, for instance, if organizations strategy is not aligned with the BPM efforts, top management doesn’t give their support for BPM efforts or the organizational culture does not support BPM (Trkman 2010; Schmiedel et al. 2013). Among other things, it’s important that employees are trained and they have access to process models and the models are actively used for example in improvements and audits (Trkman 2010; Laamanen 2003, 96-97). In the end, BPM is maturity development process and organizations should to work persistently to reach their goals (Harmon 2014, xxix; Laamanen 2003, 40-42).

Challenges of process modelling in practice

Many of the challenges that were described in the literature, were faced in the case organization while modelling the core processes of the organization. Some of the challenges that were faced, related to scheduling and resourcing. The timing of the process modeling project was somewhat challenging as a great proportion of the staff members were engaged in other extensive high-priority projects for few years’ time. While the key resources were engaged in other projects and work tasks at the same time, major changes in the plans could not be made to still be able to keep the given timeframe for the project.

In the beginning, the project team members didn’t have very good overview of the organizations processes and the complexity of the processes. Therefore, it was not clear how many core processes existed and how complex the processes were, so making estimations of the number of the needed workshops, and consequently, the needed resources, was challenging. Large proportion of the processes under the scope of this project were more complex than expected, mainly due to their interfaces with other internal processes or several IT systems. There was a tight schedule for the overall planning phase and approximately max. 10 % of the project managers resource could be used for planning.

It is recommendable to reserve more time in the planning and get the substance matter specialists of the processes involved in the planning as they have the best abilities to evaluate the content and complexity of the processes in question. In this case, almost 60 participants took part in defining and modeling of the processes. With so many participants, the project coordination with the unavoidable changes with the participants schedule required a lot of work. One of the most challenging part was to determine the needed level of detail, which equals the modeled levels. Also, the number of elements used in single process models grew sometimes perhaps unnecessary high. If possible, it’s better to work with one process or value chain at the time and reserve more time for each workshop.

Observations implied that it was sometimes difficult for the participants to apprehend what was expected of them and what kind of information they were expected to provide, thus this resulted also in the attitudes towards process modeling. In the case, only few individual participants had previous BPM experience. This indicates that more extensive training in BPM would have been needed. It is recommendable to use resources on ensuring, and if needed, increasing the BPM knowledge of the participants. More training, support and information sharing throughout the project will increase the awareness and give participants a clearer picture of the target end results.

Iteration rounds ensured that produced process models can fulfil the predetermined purpose and fit well together. Many iteration rounds were conducted in this project but on contrary to planned, considerable amount of iteration had to be done when processes where already combined in a uniform hierarchy. In the case, processes were defined in smaller groups formed by individual teams or units. It would have likely been more fruitful for the participants if the groups would have been formed based on processes and participants from different units would have worked more together.

Summary

Business process management is a holistic management approach aiming to create value through cross-organizational processes. Process modeling challenges the participants of the modeling work to seek joint understanding of the subject of modeling. There are many details to consider when starting a process modeling project and it’s wise to make good plans before the modeling work. Most importantly, the purpose of the modeling and the user groups utilizing the process models should determine the content of the models. Process modeling can challenge the traditional ways that people are used to perceive the organization’s operation so some difficulties may arise. When the most typical challenges are identified beforehand, change is managed more likely successfully. If the processes are well modeled and accessible by all members of the organization, the process models work as great tools for training, development work and management activities, among many other uses.

References

Bobrik, R. Reichert, MU. & Bauer, T. 2007, Parameterizable Views for Process Visualization. CTIT Technical Report Series, no. 1, suppl./TR-CTIT-07-37, Centre for Telematics and Information Technology (CTIT), Enschede.

Gebauer, A. (2012). Mindful organizing a paradigm to develop managers. Journal of Management Education, 37(2), 203-228.

Harmon, P. 2014. Business process change: A business process management guide for managers and process professionals. Third edition. Waltham, Massachusetts: Elsevier. Figures 2, 4 & 6 published with permission from Elsevier.

JUHTA – Julkisen hallinnon tietohallinnon neuvottelukunta. 2012. JHS 152 Prosessien kuvaaminen. Versio: 5.10.2012. [online]. Available at: https://www.suomidigi.fi/ohjeet-ja-tuki/jhs-suositukset/jhs-152-prosessien-kuvaaminen. [Accessed 1 February 2021].

Laamanen, K. 2003. Johda liiketoimintaa prosessien verkkona. 3rd Edition. Suomen Laatukeskus.

Laamanen, K. & Tinnilä, M. 2009. Prosessijohtamisen käsitteet: Terms and concepts in business process management. 4. uud. p. Helsinki: Teknologiainfo Teknova.

Luukkonen, I., Mykkänen, J., Itälä, T., Savolainen, S., Tamminen, M. 2012. Toiminnan ja prosessien mallintaminen. Tasot, näkökulmat ja esimerkit. Itä-Suomen yliopisto ja Aalto-yliopisto. SOLEA-hanke.

Ray, J. L., Baker, L. T., & Plowman, D. A. (2011). Organizational mindfulness in business schools. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(2), 188-203.

Roberts, K. H. (1989). New challenges in organizational research: High reliability organizations. Industrial Crisis Quarterly, 3, 111-125.

Rummler, G. A. & Brache, A. P. 2013. Improving performance: How to manage the white space on the organization chart. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schmiedel, T., vom Brocke, J. & Recker, J. 2013. Which cultural values matter to business process management? Business Process Management Journal, vol. 19, no. 2, 2013, pp. 292-317.

Trkman, P. 2010. The critical success factors of business process management. International Journal of Information Management. 30, Issue 2: 125-134.

Weick, K. E. (1987). Organizational Culture as a Source of High Reliability. California Management Review, 29(2), 112.

Weick, K. E., & Roberts, K. H. (1993). Collective mind in organizations: Heedful interrelating on flight decks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(3), 357-381.

Vogus, T. J., & Welbourne, T. M. (2003). Structuring for high reliability: HR practices and mindful processes in reliability-seeking organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(7), 877-903.