Story of a company which did not know what they know

This is a story about an organization in the business of high-value technology, which was seeking to have knowledge about process variation management. What did they learn about their knowledge assets?

The company, established over 100 years ago, had experienced eras colored by economical fluctuations, technological advancements, internalization and of course various projects and customers, each having their own unique characteristics and requirements.

Not long ago, the company once again found itself facing new developments. An exiting customer project was about to ramp up. The customer was asking, how does the company ensure that their manufacturing meets the requirements of product and process key characteristics? The words sounded vaguely familiar, but the company had to process the question. What did the customer really ask?

SPC and Key Characteristics

The customer was talking about statistical process control (SPC) which is a set of tools for continuous improvement launched nearly a decade ago. SPC aims to manage and improve processes and has been successfully adopted by multiple industries (Merriman, 2021; Salomäki, 2003). The tools, such as control charts, enable the organization to observe the behaviour of their processes and identify variation. Perhaps the most important benefit is to be able to react before variation leads to non-conforming process outputs and customer dissatisfaction. Based on statistics and probability theory, SPC gives the organization data-driven methods to eliminate sources of variation and support their decision-making.

Key characteristics (KC) work as an important steering aid in variation management. There are two kinds of key characteristics:

- Product KCs, they tell which characteristics (for example geometrical or functional) of a product are those whose variation must be controlled to ensure customer requirements are met.

- Process KCs are those process characteristics (such as temperature, pressure or time) whose control is primary to manage the variation of product KC.

Control in this context means gaining an understanding of what causes variation to the KC’s and applying SPC methods to keep the variation on an acceptable level. (Madrid, 2020; SAE International, 2022; Salomäki, 2003)

According to the company’s tradition there had been one customer earlier asking the same question, but it was not clear what answer had been given and if it had been correct. This was because today no related inhouse expertise, standard procedures, tools or methods could be pointed out. The company had gone through streamlining projects during the years and developed towards lean, which is a close-related ideology. Still, the course of action applying variation management or interest towards key characteristics was not quite rooted. It seemed the company had now fallen into a pit of tacit knowledge.

Tacit knowledge

The company decided to approach the problem by deep diving. A study was completed to figure out what the organization knows about the topic. But what was the company actually after? According to Polanyi (1966, 1998) tacit knowledge can be described as silent, not comprised and not easy to explain-knowledge. Examples are skills, attitudes and behaviours (Handa et al., 2019). Nonaka (1994) clarified the definition further by comparing it to as evenly important explicit knowledge; the knowledge which can be expressed with words, symbols, drawings, scripts, and so on. Especially Nonaka (1994) underlined the criticality of converting the tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge and vice versa for the sake of organizations’ innovations and ability to learn. Nonaka’s observation was on point, the company had to reveal the tacit knowledge and make it explicit, to be able to utilize it.

Problem definition

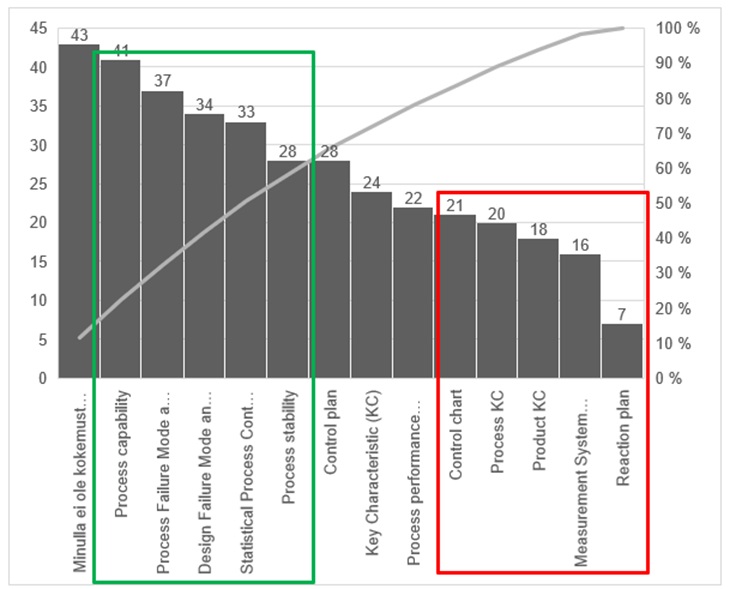

To be able to investigate the subject, the company had to define the problem: what hidden and/or gaps of knowledge does the company have about variation management? Standard AS9103 Variation Management of Key Characteristics (SAE International, 2022), which focuses on the requirements of capabilities and KC’s of the manufacturing and assembly processes, set the framework and terminology used in the study. To be able to reveal the information of knowledge level of the company and not to limit the answers too much, it was important to do both: ask the respondents knowledge of specific variation management related terminology (see Figure 1) and provide them with open questions. It had to be conducted so that even the people who think they have zero knowledge of the topic would be willing to answer. Additionally, the survey study had to reach across the limits of different business units and organizational levels.

The knowledge assets identified

The study resulted in over 100 responses from staff members describing their level of knowledge of variation management. To understand and structure the results a knowledge asset-model by Handa et al. (2019), originally developed for auditing knowledge assets of organizations, was used. According to Handa et al. (2019), the knowledge of an organization can be divided into three assets:

- Human,

- Structural, and

- Relational.

Each asset is divided into sub-categories to describe the knowledge in question in more detail. The study results matched with each asset category. Human-category included the respondents’ work experience and gained competence as in Black, Yellow and Green Belt- qualifications – information, which was warmly welcomed. SPC-data from former projects and programs as well as the written SPC-procedures and related methods could be identified as structural knowledge assets. Relational knowledge assets were not emphasized in results, but for example the connection between the study subject and the company wide Lean Six Sigma (LSS) program could be registered in this category.

First surprise

The study results astonished by providing variety of practical targets, where the respondents saw variation management could solve problems. According to the respondents, variation management could come in place in

- Lead-time management of different functions, such as maintenance services and handling of quality issues, to increase their effectivity

- Decreasing the variation originating from measurements to improve product quality

- Minimizing the variation of the supplied products and delivery time for improved supplier control

- Process studies to identify the process phases where the variation management could benefit the most

- Improvement of tolerance management of physical products

- Study and elimination of variation involved with material storage conditions to make them more stable

- Study and elimination of variation involved with all kinds of production, to improve the accuracy of delivery dates and customer satisfaction, and

- To gain better understanding of the influence of clear work instructions and their change management to the product/service variation.

These ideas verified the knowledge the company was seeking exists inhouse. Most importantly, there appeared being a positive attitude among respondents towards continuous improvement.

Second surprise

Another unexpected study result were the hints of explanations why the variation management, lean and related ideologies had not become established earlier in the company. The study results contained appropriate, yet subtly frustrated descriptions of colleagues with a less-than-enthusiastic interest in participating in process development. There were also description of department repeating the same mistakes with raw material quality as a modus operandi, instead of eliminating the root causes behind. The organizational culture was described with a similar tone, there were voting for to implement the variation management systemically with a top-down approach in place of thus far applied “fire and forget”-mentality. All in all, the general opinion seemed being that the company “had still a lot to learn”. Pearce et al. (2018) have suggested that successful lean implementation in small to medium-sized (SME) enterprises depends on the leadership knowledge, more specifically the leadership’s attitude and commitment, towards learning. Could it be the case also with larger companies?

Final answer

Finally, the company was ready to give their answer to the customer. It was: “We now know what to do to meet the requirements of key characteristics and control variation management; we have the procedures and even expertise for that. We also know where we still lack knowledge and what mistakes to avoid, so luckily, we still have something to improve. When can we start? “

The study had made it visible that the company knows about variation management, had tried it before but failed to fully adopt. The gaps of knowledge were also identified in the study, so it was now possible to start filling them. The study showed the company had taken notes from the earlier mistakes and shown to be eager to apply variation management again, to learn and improve.

References:

Handa, P., Pagani, J., & Bedford, D. (2019). Knowledge assets and knowledge audits. Emerald Publishing.

Madrid, J. (2020). Design for Producibility in Fabricated Aerospace Components – A framework for predicting and controlling geometrical variation and weld quality defects during multidisciplinary design.

Markkanen, S. (2024). Variation management in aerospace industry : gap analysis for AS9103. Master’s Thesis. Turku University of Applied Sciences.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37.

Pearce, A., Pons, D., & Neitzert, T. (2018). Implementing lean: Outcomes from SME case studies. Operations Research Perspectives, 5, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orp.2018.02.002

Polanyi, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Polanyi, M. (1998). Personal knowledge : towards a post-critical philosophy. https://web.archive.org/web/20240804103518/https://books.google.fi/books?id=0Rtu8kCpvz4C&pg=PP9&hl=fi&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

SAE International. (2022). AS9103B: Aerospace Series – Quality Management Systems – Variation Management of Key Characteristics.

Salomäki, R. (2003). Suorituskykyiset prosessit – hyödynnä SPC (2.). Metalliteollisuuden Keskusliitto, MET.

Picture: Wikimedia Commons

Figure: Markkanen, S. (2024). Variation management in aerospace industry : gap analysis for AS9103. Master’s Thesis. Turku University of Applied Sciences.